Spartans Track and Field Host Annual Solomon W. Butler Classic

Jan 16, 2015

DUBUQUE, Iowa - The University of Dubuque will host the annual Solomon W. Butler Classic Track and Field Meet on January 17 on A.Y. McDonald Indoor Track in the Chlapaty Recreation and Wellness Center. Teams scheduled to compete are: the University of Dubuque, Augustana College, Carroll University, Clarke University, Coe College, Cornell College, Loras College, Monmouth College, North Iowa Area Community College, Southwestern Community College, and William Penn University.

Field events begin at 10:00 a.m. and running events start at 11:00 a.m. Tickets are $6 for adults and $3 for students and doors open at 9:00 a.m.

Race Results provided by accuracetiming

Tentative Schedule for Solomon W. Butler Classic:

9:00 a.m. Doors Open for fans - Seating available on the mezzanine level of Chlapaty Recreation and Wellness Center

(Only student-athletes, coaches, and meet staff will be allowed on the track and competition area, thanks for your cooperation.)

10:00 a.m. Implement Weigh In (Equipment Room Check-in Window)

Field Events

10:00 a.m. Weight Throw – (W/M) Shot Put follows (W/M)

10:00 a.m. Long Jump – (W/M) Triple Jump follows (W/M)

10:30 a.m. High Jump – (M/W)

Pole Vault – (W/M)

Running Events

11:00 a.m. Running events begin (Note - ROLLING SCHEDULE after the mile run)

11:00 a.m. 4x800 meter relay

11:45 a.m. 55 meter high hurdle prelims

12:15 p.m. 55 meter dash prelims

12:45 p.m. mile run

1:25 p.m. 55 meter high hurdle finals (*men run first)

1:35 p.m. 55 meter dash finals

1:45 p.m. 400 meter dash

2:10 p.m. 3000 meter run – women’s

2:30 p.m. 3000 meter run – men’s

3:00 p.m. 4x200 meter relay

3:15 p.m. 600 meter run (two turn stagger in lanes)

3:35 p.m. 200 meter run

4:00 p.m. 4 x 400 meter relay

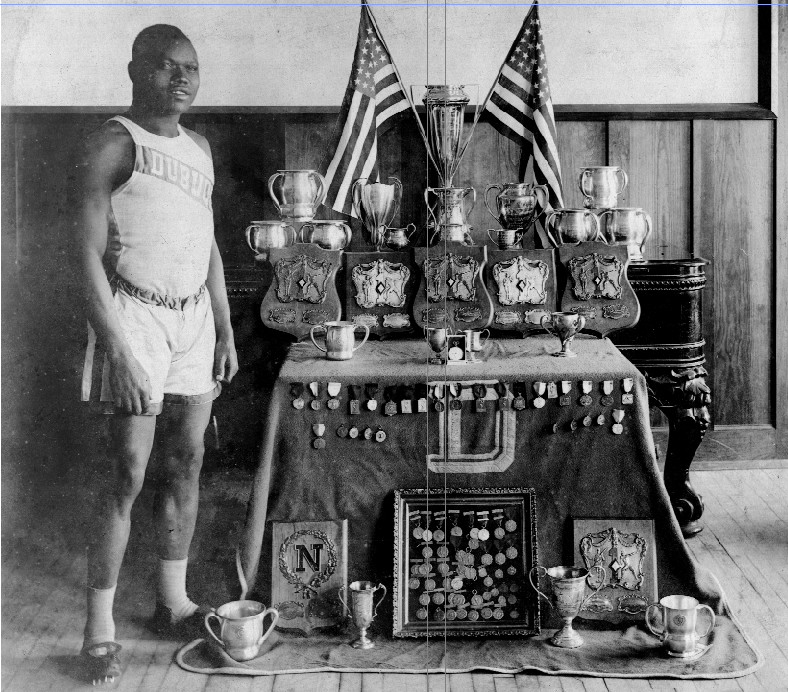

Solomon Wellings Butler was born in Kingfisher, Okla. on March 3rd of 1895, the youngest child of Ben and Mary Butler. His father was from Morgan County, Alabama and born a slave in 1842, his mother was born in Georgia in 1867. His father fought in the Civil War and took the last name of Butler from General Butler whom he admired. The Butler family escaped slavery and settled in Wichita, Kansas before moving to Hutchinson, Kansas in 1909. “Sol”, as he was known made the varsity football team as a starting halfback during his freshman year. He led the school in football and in track and field. His sophomore year he helped Hutchinson to a runner-up finish at the state meet after setting state records in the 100 yard dash. In 1913, as a junior in Hutchinson High School (Kans.) he dazzled spectators at the district meet where he won six firsts, broke five meet records and unofficially breaking a world record in the 50 yard dash. He along with his older brother Benjamin would follow his high school coach to Rock Island, Illinois for his senior season in 1914. Facing 300 of the best track stars of the Midwest in Chicago, he competed in the regional interscholastic meet held at Northwestern University. On an unfriendly soil, the son of a freed slave, placed in the 60 yard dash and hurdles, the 440 yard dash, and also in the broad jump. He broke one meet record, tied a world record, and won fourth placed overall, competing against entire track teams!

Butler earned 12 varsity letters competing in Football, basketball, baseball and track and field at the University of Dubuque from 1915-19. According to Arthur Ashe Jr.’s book, Hard Road to Glory, A History of the African-American Athlete, Butler was the first African-American to quarterback a team for all four years of college. In Butler's day, the track and field of activity was restricted. There was no national collegiate meet and very little indoor competition. Even the Drake Relays, then in their formative years, provided no such event as the broad jump. Butler was forced to the Penn Relays for that competition and twice won the championship. In 1919, to illustrate, Butler won both the 100-yard dash and broad jump at the Penn Relays.

Entering military service as a soldier in World War I as he represented the U.S. Army in the Inter-Allied Games in Paris. He won the broad jump and placed in the 100-meter dash. He was knighted by the King of Montenegro, who made Butler a Knight of the Third Order of Danilo. And with the Olympic Games scheduled for renewal in 1920 after the wartime interruption in 1916, Butler was rated as a heavy favorite for the championship. His winning jump at Paris, 24-9 1/2, was only two inches from the Olympic record and was considered a strong possibility for a new Olympic record. Butler went to Antwerp for the 1920 Olympics, but misfortune nailed him quickly. On his very first jump in the Olympic preliminaries he pulled a tendon and was forced to withdraw. The injury-hampered effort was a shade under 21-8. He won the U.S. National Amateur Athletic Union championship that same year by broad jumping 24-8. The Olympic experience was a heartbreaker for Butler.

He signed on with the NFL in 1923 with the Rock Island Independents which local accounts raved about his first apperance in the victory over the Chicago Bears. His contract from Rock Island was sold to the Hammond Eleven in November of 1923 for the remainder of the season for $10,000. Butler played alongside Jim Thorpe of the Canton Bulldogs where he was named starting quarterback in 1926. In 1926, the New York Giants refused to let it’s all white team on the field in front of the largest crowd ever (40,000) to watch an NFL game until Canton withdraw Butler as starting quarterback. While in California playing for the Chicago All-Stars basketball team which he founded, he would stay in the state. Butler used his earnings to re-open Jack’s Cafe, previously owned by Jack Johnson, former heavyweight boxing champion in 1932.

He was named to a key role in a film by Russ Sanders in 1935 being filmed in Hollywood, Calif. after playing minor parts in a few films prior. He was signed by Oscar Devereaux Mischaux, and independent producer of more than 44 films for Lincoln Motion Picture Company. Butler moved back to the Midwest and went on to work with the youth in the Negro districts as recreation director of Chicago's Washington Park. He worked part-time as a probationary officer, and became sports editor for the Chicago Bee and The Defender newspapers in Chicago. He and his brother Ben, sold cars, self-published a book on track and field, shined shoes, and did anything they could to raise money. In his later years after prohibition, Butler owned nightclubs in Chicago, set up his own talent agency and and for a brief period was in the record business representing Paul Robeson, an American singer and actor who was a political activist for the Civil Rights Movement.

Unfortunately for Butler, his life came to a tragic end on Dec. 1, 1954 in Paddy’s Liquors, a Chicago tavern where he was employed for seven years. Butler met his death by a man named Jimmie Hill, who reportedly had been annoying two female patrons. Butler ejected Hill, who came back with a gun and shot the former star in the hip and chest. Butler died of his injuries at Chicago's Provident hospital.